David Branch, Sector Manager, Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute

Each year Americans consume the equivalent of 20 pounds of chocolate per person. Couple this with the rising global demand projected to reach 7.5 million metric tons or 16.8 billion pounds in 2023, and you could say that our appetite for chocolate has never been healthier.

Each year Americans consume the equivalent of 20 pounds of chocolate per person. Couple this with the rising global demand projected to reach 7.5 million metric tons or 16.8 billion pounds in 2023, and you could say that our appetite for chocolate has never been healthier.

However, as demand has risen, so has cost. Part of this is due to basic economics of supply and demand - higher demand combined with flat or constrained raw material supply has pushed up product costs and the related market price. And, while some of these dynamics could subside, others may persist.

Unwrapping the rising costs

To some extent, chocolate’s escalating cost can be understood by looking at the overall rise in product manufacturing costs, with the Producer Price Index (PPI) for Food Manufacturing increasing 28% since January 2020. This rising inflationary environment has increased the cost of labor, processing, manufacturing, packaging, and transportation. Higher raw material costs for two of chocolate’s crucial ingredients - sugar and cocoa - are also included in this overall cost increase.

A sweet and sour look at sugar

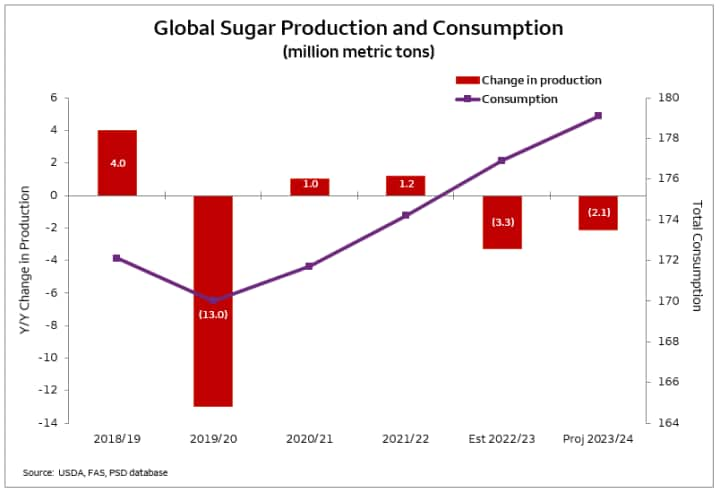

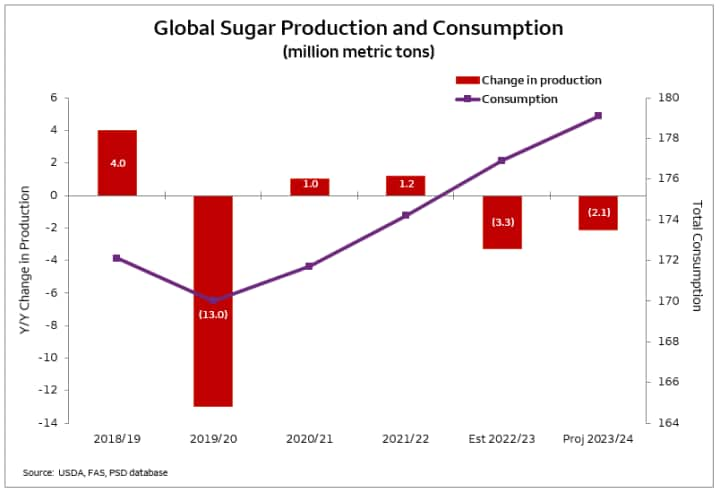

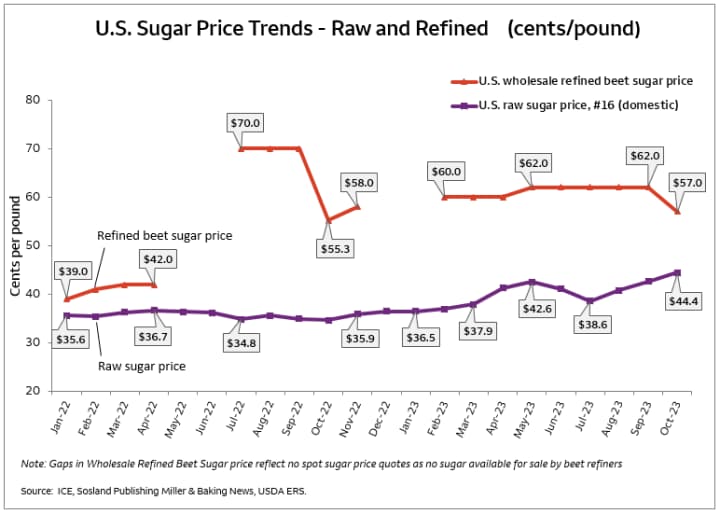

Global sugar prices are at levels not seen since February 2011. The current raw sugar price has rallied, and is currently trading at levels above the U.S. raw sugar futures prices. This rally is the result of flat-to-negative U.S. beet/cane production since 2020, causing the U.S. to import more sugar from global markets coupled with flat-to-negative global production.

Starting with the 2019/20 crop year, total production declined 13% due to drought in Brazil, Thailand, India, and Mexico, resulting in declining global sugar production, and this trend is not forecasted to reverse any time soon. Due to the current El Niño weather pattern, tending to result in drier and warmer temperatures, overall global production for the 2023/24 crop year is forecasted to decline by 2.12 million metric tons with lower projected production in India, Thailand, and Australia. This has continued to drive the rally in global markets as growth in consumption combined with a projected decline in production will continue to put upward pressure on pricing.

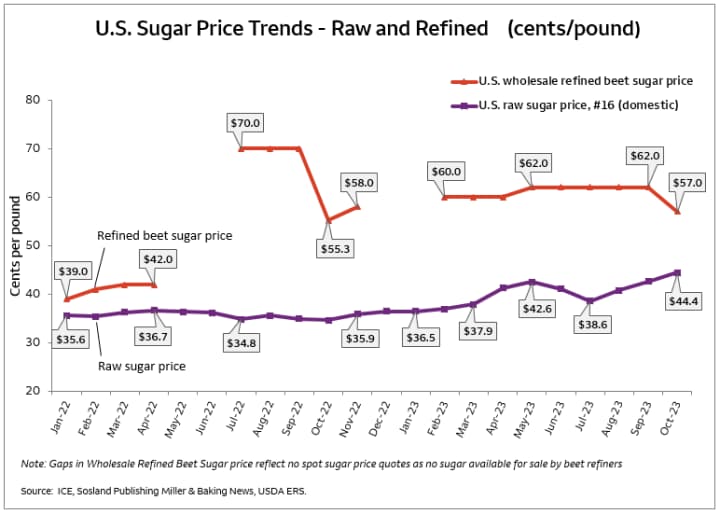

The U.S. sugar market has also experienced significant volatility in the past few years due to multiple factors including supply issues, increasing domestic consumption, and overall inflationary pressures. All of these things have contributed to the current elevated pricing for refined sugar. Refined sugar prices dropped in October 2023 to 57 cents per pound after hovering around 60 to 62 cents per pound when a significant run-up began in April 2022 due to shortages in the beet crop harvest in some growing areas. The resulting scramble to replace the cancelled sugar volume pushed up spot prices by 107%, to 70 cents/lb., in July of 2022.

How climate is impacting a fickle cocoa crop

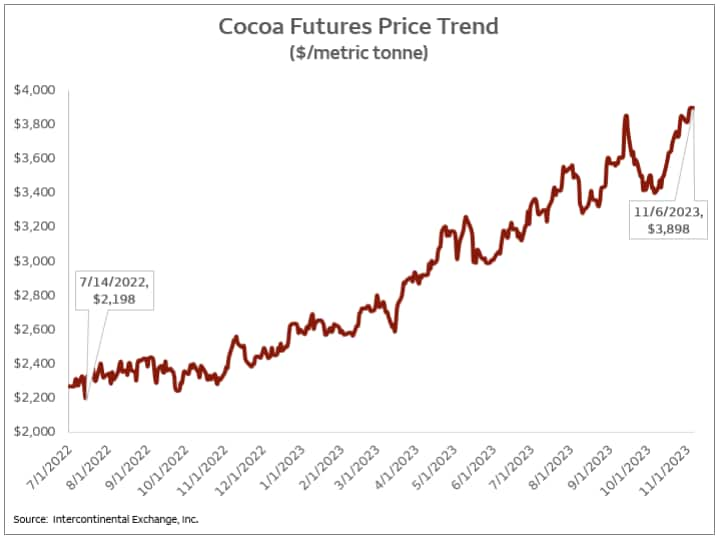

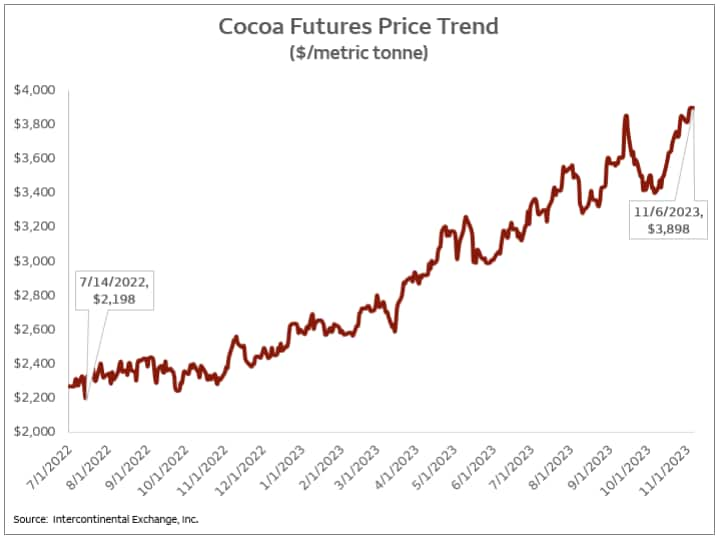

Like sugar, cocoa prices are also up. But, unlike sugar, we may not see prices cycle down anytime soon as changing weather patterns are continuing to have a negative impact on cocoa supply.

While sugar is produced from sugar cane and sugar beets that can be grown in various climates, cocoa trees only grow within 20 degrees of the equator (north and south). Cocoa trees require specific weather conditions including even temperatures between 69.8 degrees and 73.4 degrees Fahrenheit, high humidity, fairly constant rain of 39.4 to 98.4 inches per year, nitrogen-rich soil, and protection from hot, dry winds and drought. For this reason, cocoa is produced predominantly in the hot and humid region of Africa, which produces more than 70% of the world’s supply, followed by Central and South America at 15%, Asia at 13%, and Australia at 2% respectively. Given this significant concentration of supply in a single agricultural area, global cocoa production is especially vulnerable to climate change since there is not much room for error.

The impact of changing weather patterns on cocoa production was first mentioned in 2014 following a research study that predicted that average temperatures in cocoa’s growing regions would rise by 3.8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, reducing the amount of acreage suitable for cultivation. This conclusion was based on the premise that the rising average temperature would impact the soil moisture available for the crop as well as reduce the average rainfall in the area that would typically compensate for the higher temperature. The Ivory Coast produces about 50% of the global cocoa bean harvest with Ghana, Cameroon, and Nigeria accounting for an additional 25%. With above-average rainfall last crop season resulting in increased disease issues, West African growers are now dealing with the current El Niño, projected to remain until mid-2024, threatening this year’s crops. Previous El Niño years have led to overall drier conditions resulting in lower cocoa yields.

The result of these continued weather issues on cocoa bean production has current cocoa futures trading at historic highs. The futures price quote, as of November 3, 2023, was $3,865 per metric ton, up 60% year over year, and up more than 77% since July 14, 2022, based on a projected production deficit for a second consecutive growing season. This could push the overall global cocoa stocks lower.

Taking the bitter with the sweet

So, while many of the inflationary pressures impacting the rising costs of chocolate should begin to subside, the industry needs to remain focused on the effects of a changing climate on the cocoa crop to ensure continued supply for one of our favorite confections. At issue is the fact that the industry is made up of approximately six million farmers with more than 90% of those cultivating cocoa on land averaging 12 acres in size. Given this scenario, it’s challenging to determine what farming techniques can be implemented to safeguard cocoa protection when farmers at the core of the industry make barely enough money to survive.

Decades of research by the confection industry in partnership with non-profit groups and government agencies has concluded that the approach to cocoa farming must change if the industry is to remain viable for the next 20 years. This will require the reversal of decades of monocropping and deforestation practices, replacing them with agroforestry, the practice of intercropping beneficial trees and other crops alongside cocoa trees. Agroforestry cocoa can support climate change mitigation by sequestering carbon, conserving biodiversity, improving soil fertility, and controlling pests and diseases, all while providing a favorable microclimate where temperature and moisture are regulated by the forest. While transitioning an entire industry from monoculture to agroforestry will be an uphill battle, continued financial and technical support from groups like Trees for the Future, World Cocoa Foundation, and the Cocoa and Forests Initiative - a collaboration between 35 major cocoa companies and producer-country governments - is key to ensuring future supply of our coveted chocolate confections.

David Branch is a Sector Manager within the Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute focused on seafood/aquaculture, nursery/greenhouse, sugar, and other specialty crops.

David Branch is a Sector Manager within the Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute focused on seafood/aquaculture, nursery/greenhouse, sugar, and other specialty crops.

David possesses greater than 30 years of lending experience. Prior to joining Wells Fargo, he worked for the Bond & Corporate Finance Group at John Hancock Financial Services where he was responsible for originating and servicing loans and private equity investments in the forest products, building materials, timber, and paper industries throughout the US, Canada, Europe, South America, and the Pacific Rim. Previously, he worked at Travelers Insurance Company and CoBank.

David graduated from Louisiana Tech University with a Bachelor of Science. in Forestry and earned a Master of Science in Forest Economics from Louisiana State University. David currently serves on the board of The Frank Norris Foundation, a non-profit foundation that publishes the Timber-Mart South© quarterly newsletter and price reports.

Sign On

Sign On  Each year Americans consume the equivalent of 20 pounds of chocolate per person. Couple this with the rising global demand projected to reach 7.5 million metric tons or 16.8 billion pounds in 2023, and you could say that our appetite for chocolate has never been healthier.

Each year Americans consume the equivalent of 20 pounds of chocolate per person. Couple this with the rising global demand projected to reach 7.5 million metric tons or 16.8 billion pounds in 2023, and you could say that our appetite for chocolate has never been healthier.

David Branch is a Sector Manager within the Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute focused on seafood/aquaculture, nursery/greenhouse, sugar, and other specialty crops.

David Branch is a Sector Manager within the Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute focused on seafood/aquaculture, nursery/greenhouse, sugar, and other specialty crops.