March 11, 2025

Michael Swanson, Ph.D., Chief Agricultural Economist, Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute

Getting ‘food fluent’ by understanding personal consumption expenditure (PCE)

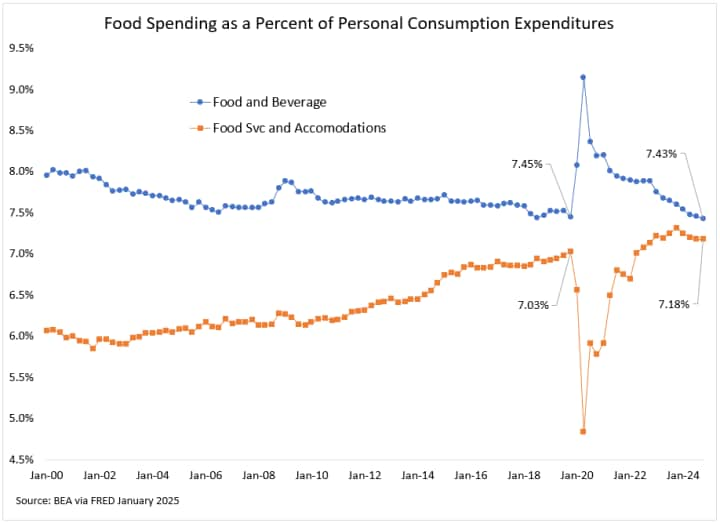

The U.S. consumer has never spent more money than during the recently ended fourth quarter of 2024. Between employment growth and wage inflation, the top line for spending continues to grow quickly increasing 5.7% from a year ago. The annualized rate of spending for personal consumption expenditure clocked in at $20.3 trillion dollars in the fourth quarter. It’s an amazing thing when you need to round to trillions, but that fact shows how large the U.S. economy really is. The fourth quarter statistics for food and beverages purchased for off-premise consumption, (that’s a long name for supermarkets), was $1.5 trillion. That works out to 7.43% of PCE spending was on food and beverage purchases in supermarkets. This is the lowest percentage ever recorded since the Bureau of Economic Analysis started keeping records. It just edges out the 7.45% in the fourth quarter of 2019, prior to the COVID disruption. Many consumers will simply disbelieve the statistics since it isn’t their lived experience. Headline after headline emphasizes record high food prices for items like eggs and chocolate, but a couple of grocery items do not represent the entire category. Regardless, when we look at the percentage of how much consumers are spending on food at the supermarket compared to the percentage they are spending on other expenditures, 7.43% is the lowest percentage spent on food that we’ve seen.

Whether the consumer believes it or not, this is the continuation of a long running trend. In 1959, when the BEA started collecting statistics for food and beverage purchases for off-premise consumption, the category accounted for 19.4% of total personal consumption spending. Roughly, one out of five dollars went for this category making it a true driver of overall inflation and economic well-being. The food was very straightforward with most people purchasing simple and basic ingredients to cook and bake with at home. Today, the variety and quality of foods sold at the supermarkets would stun a shopper from 1959, and if you adjusted the prices for the level of income it would look cheap for almost all categories.

Convenience is the consumer’s favorite flavor

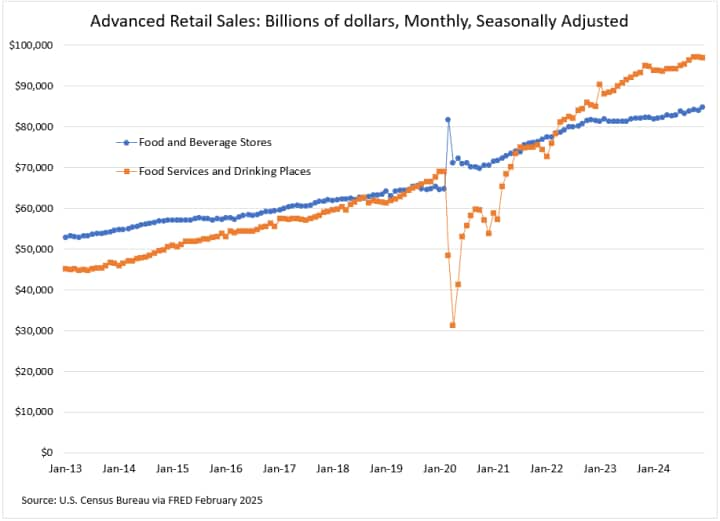

Those consumers have responded to this savings by spending more and more dollars away from home for food. The BEA puts that spending away from home into the food services and accommodation category (shown in the chart above), which makes it hard to separate the food portion from the accommodation portion. We can use the Advance Retails Sales data series, (shown in chart below), to get a picture of that breakout with more clarity. Spending on food services and drinking places achieved parity with food and beverages stores in 2018, and it surpassed food and beverage stores in 2019 just prior to the COVID shutdowns. In the beginning of 2022, it recovered and blew past food spending for home consumption. It has not looked back, and food spending away from home continues to grow faster. If actions speak louder than words, the U.S. consumer isn’t really all that concerned about food expenses and stretching their food dollar, if it means compromising on convenience. It should go without saying that some segments of the consumer population don’t fit into this spending pattern, but they are the exception not the rule.

Why this is important for the food industry

So, what is the takeaway for the food industry? The answer is full speed ahead for product introductions and packaging innovations. Yes, the consumer wants healthy food, but they will always choose it in the easiest format to prepare and eat – even if that means ordering take out. The food industry knows that consumers want to be able to go from refrigerator or freezer to the dinner table in minutes with minimal preparation. The consumer expects the shelves, refrigerators, and freezers to be full of their favorite items and they want options for flavors and packaging size. This will be a reversal of the COVID caused reduction in production offerings that temporarily helped reduce manufacturing and retailing complexity. Supply chains are back to their “just in time” focus with higher interest rates making inventory more expensive. It is time to dust off your playbook from the end of 2019 before COVID hit. The U.S. food ecosystem is back to its focus on creating value by convenience.

Michael Swanson, Ph.D. is the Chief Agricultural Economist within Wells Fargo's Agri-Food Institute. He is responsible for analyzing the impact of energy on agriculture and strategic analysis for key agricultural commodities and livestock sectors. His focus includes the systems analysis of consumer food demand and its linkage to agribusiness. Additionally, he helps develop credit and risk strategies for Wells Fargo’s customers, and performs macroeconomic and international analysis on agricultural production and agribusiness.

Michael Swanson, Ph.D. is the Chief Agricultural Economist within Wells Fargo's Agri-Food Institute. He is responsible for analyzing the impact of energy on agriculture and strategic analysis for key agricultural commodities and livestock sectors. His focus includes the systems analysis of consumer food demand and its linkage to agribusiness. Additionally, he helps develop credit and risk strategies for Wells Fargo’s customers, and performs macroeconomic and international analysis on agricultural production and agribusiness.

Michael joined Wells Fargo in 2000 as a senior economist. Prior, he worked for Land O’ Lakes and supervised a portion of the supply chain for dairy products, including scheduling the production, warehousing, and distribution of more than 400 million pounds of cheese annually, and also supervised sales forecasting. Before Land O’Lakes, Michael worked for Cargill’s Colombian subsidiary, Cargill Cafetera de Manizales S.A., with responsibility for grain imports and value-added sales to feed producers and flour millers. Michael started his career as a transportation analyst with Burlington Northern Railway.

Michael received undergraduate degrees in economics and business administration from the University of St. Thomas, and both his master’s and doctorate degrees in agricultural and applied economics from the University of Minnesota.

Sign On

Sign On